Nearly one-third of employees feel spied on at work according to a recent study by HR software company ADP. A practice that results in increased stress and, paradoxically, decreased productivity. Surprise: it’s not remote work’s fault! Explanations.

Employee surveillance at work is nothing new… but it has acquired new tools with the rise of remote work and AI.

In France, a real estate company was thus fined last February for having continuously filmed its employees in its premises with permanent image and sound capture and for having configured software that tracked time spent on certain websites for those working remotely. A practice deemed too intrusive by the legislator.

The HR and payroll software company ADP looked into this phenomenon and its consequences through a vast study conducted among 38,000 employees in 34 countries.

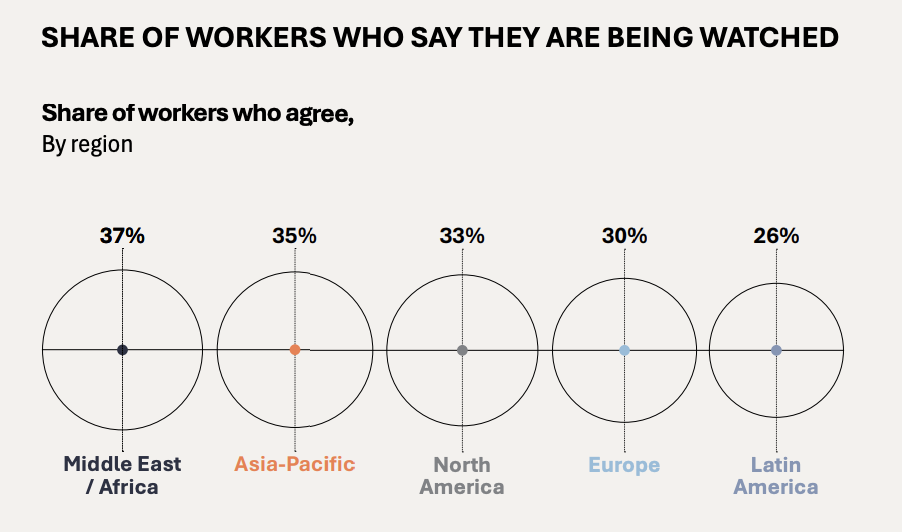

The striking result: nearly one-third of respondents indeed feel monitored at work.

Is remote work to blame?

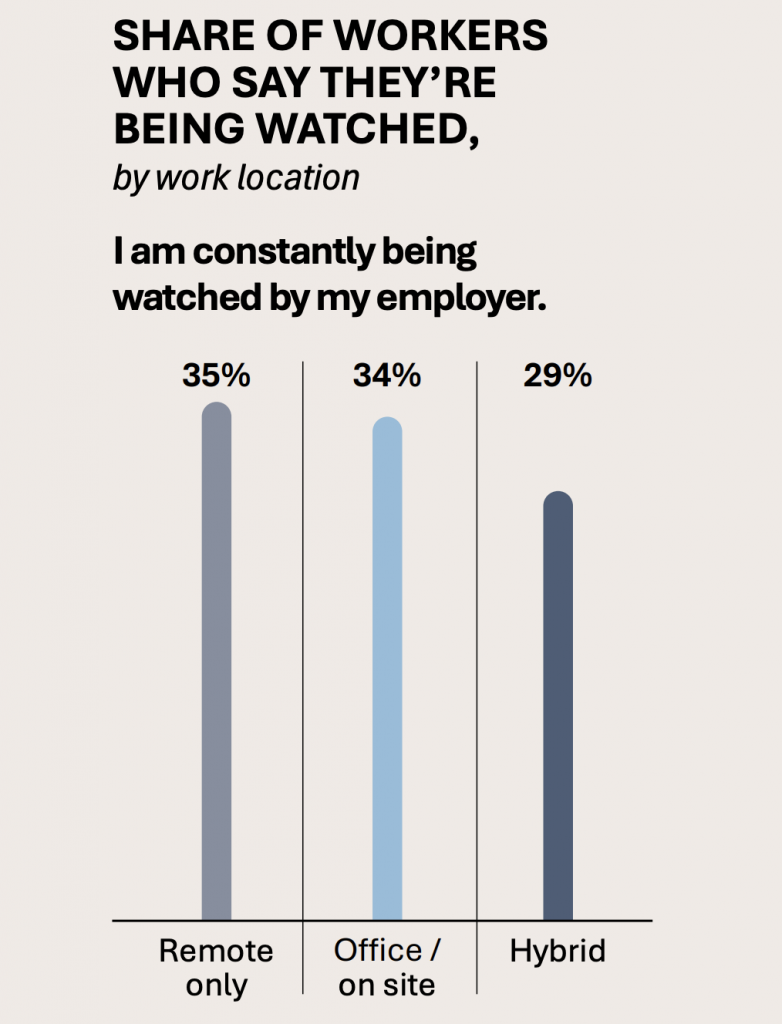

One might indeed think that not being in the office under the direct gaze of colleagues or one’s manager could encourage an employer to increase surveillance. Yet… this is not the case!

According to the survey, there would be absolutely no difference between remote workers and those who go to the office.

Let’s note in passing that, according to Statistics Canada, the proportion of Canadians working primarily from home has been declining for a fourth consecutive year (from 18.7% in May 2024 to 17.4% last May).

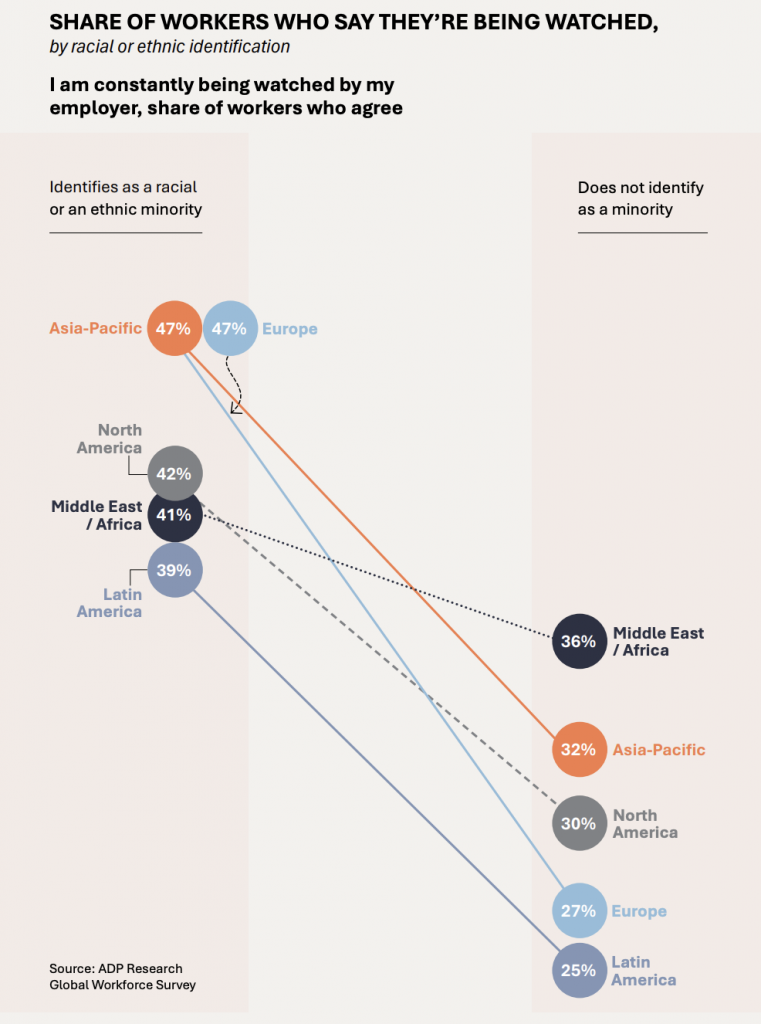

The reality is unfortunately more trivial: the main factor explaining the difference in surveillance between employees concerns… the person’s feeling of being a minority. The more an employee considers themselves a minority, the more likely they are to feel spied on at work.

The gap is particularly notable in Italy (from 61% to 24% between minorities and non-minority members). Even if it is present to a lesser degree worldwide, whether in the United States (43% and 30% respectively), Canada (41% and 30%), or France (41% and 26%).

Among other surveillance factors, note:

- Age: employees under 40 feel more monitored (37%) than those over 40 (27%)

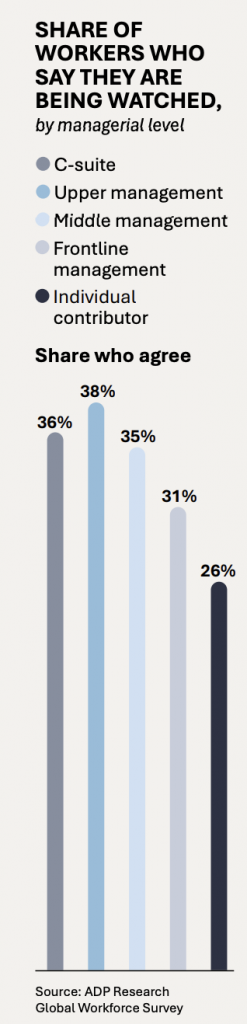

- Hierarchical level: managers and leaders feel more spied on

Harmful Consequences

Beyond the observation, let’s look at the effects of excessive surveillance. On one hand, employees who feel monitored are three times more likely to experience daily stress at work. Among them, 37% are actively looking for a new job – compared to 13% for people who experience stress less than once a week.

Moreover, “spied on” employees are also three times less likely to say they are very productive. Contrary to what one might think, monitoring teams does not increase their productivity.

“It’s false to think that to be high-performing, people must be monitored and controlled. In fact, it’s quite the opposite for the vast majority of people. Surveillance can harm the establishment of a climate of trust and autonomy,” warns Manon Poirier, Executive Director of the Ordre des CRHA in a column published in La Presse last March.

Before continuing:

“In general, employers should favor measuring results rather than micromanaging processes. Moreover, attendance is not synonymous with productivity. I invite organizations to adopt a posture of trust toward all members of their teams, and to manage exceptions as needed.”

This is also the message that ADP experts are trying to convey in their analysis report:

“Employers can reassure worried workers by communicating expectations openly and frequently. People who clearly understand what is expected of them at work are 3.7 times more likely to report being highly productive.”

In other words, what’s important for employers is to manage to measure what matters and for the employee to be able to influence this success indicator. Example: in a restaurant, the number of orders is not a good indicator for measuring a server’s work. If there are no customers, it’s not the server’s fault! A good indicator would rather be the time it takes to take an order.

“In any case, we note that generalized surveillance policies seem to do more harm than good,” conclude ADP researchers.

training.isarta.com

training.isarta.com