The desire to separate the concepts of speed and productivity is not new. The most famous illustration likely comes from La Fontaine’s fable, “The Tortoise and the Hare.” In his new book, American computer science professor and blogger Cal Newport makes a compelling case for the thesis that it is better to “do less to do better.” Explanations follow.

In a hyperconnected world where performance is king, Cal Newport stands out with books like Digital Minimalism and Deep Work, where he encourages workers to disconnect from social media to lead healthier and more fulfilling lives. In his new book titled Slow Productivity: The Lost Art of Accomplishment Without Burnout, released last March, he revisits the very concept of productivity, which he believes is ill-suited to our times.

“Our current definition of productivity is flawed,” he announces on the back cover of his book. “It pushes us to consider being busy as a measure of useful effort, leading to endless to-do lists and meetings. We are overwhelmed by everything we have to do and on the brink of burnout, left with the choice of either joining a soul-sapping hustle culture or giving up all ambition. But are those really the only choices?”

In his book, Cal Newport proposes applying the vision of Italian Carlo Petroni—who popularized the concept of “slow food”—to the world of work. Newport’s “slow productivity” is based on three principles:

- “Doing fewer things”

- “Working at a natural pace”

- “Focusing on quality”

“If you’re not obsessed with the quality of what you do, then I agree, might as well just send a lot of emails,” he quips in an interview with Adam Grant. “It’s this obsession with quality that gives meaning to the other two principles,” he explains.

Returning to the Bohemian Spirit of Artists

Slow productivity stems from a reflection on the evolution of the concept of productivity in recent decades. For Cal Newport, it’s futile to try to measure productivity the same way in a factory [by cutting and optimizing every gesture and process] as in the knowledge industry [where complexity and creativity vary greatly from one task to another].

“If we see knowledge workers as people sitting at a desk writing, we cut ourselves off from traditional wisdom that could be relevant for a distinctly modern type of activity. By drawing on Petroni’s analytical framework, we should consider a broader definition of productivity,” he asserts.

The American researcher defines productivity in the knowledge industry as: “economic activity in which knowledge is transformed into artifacts with market value through cognitive effort.” The interest of this definition is to place in the same category of “cognitive” productivity both white-collar professions like programmers, accountants, or managers and traditional professions like writers, artists, scientists, or musicians who have always enjoyed great freedom in managing their schedules.

“It’s precisely this traditional freedom that is interesting for our productivity project; because [artists and scientists] have always benefited from the time and space required to experiment and find what works best when it comes to sustainably creating things of value using the human brain,” he writes.

Cal Newport does not propose a “copy-paste” of what artists or scientists do to produce their works. Instead, the idea is to extract the general principles and transpose them into a more pragmatic context of the knowledge sector, the author clarifies.

“There is a lesson to be learned in slowing down before tackling a big project,” he argues.

For Cal Newport, the issue is to reduce not the number of hours (he is skeptical about the four-day workweek) but the workload of each person. In short, he proposes taking more time to do better. Easier said than done!

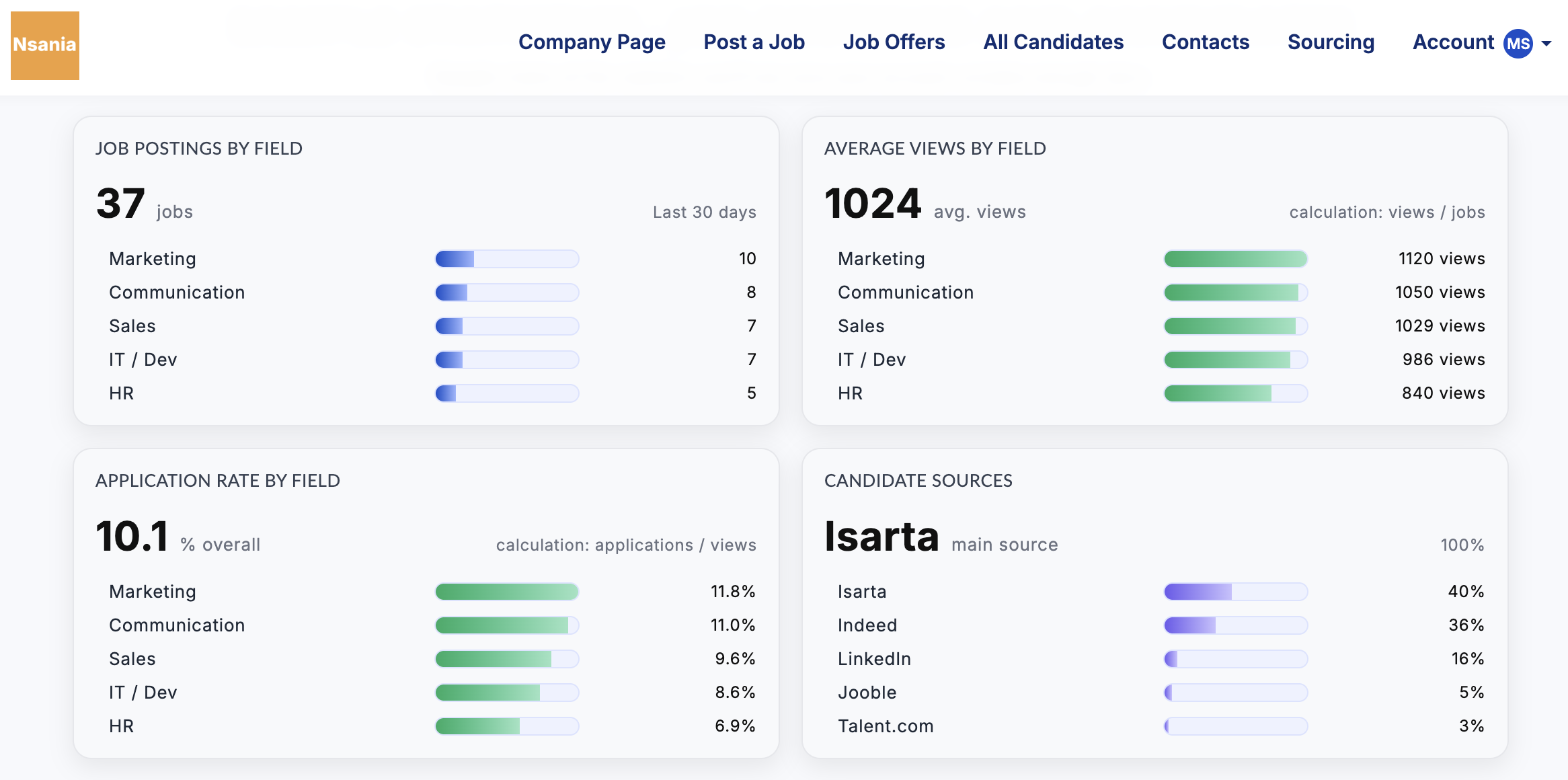

Discover our training :

training.isarta.com

training.isarta.com